120 Free Spins Story

In 2012 Pixar Story Artist Emma Coats tweeted 22 storytelling tips using the hashtag #storybasics. The list circulated the internet for months gaining the popular title Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling. We reposted this list two weeks ago and the response has been phenomenal with thousands of likes, shares, comments and emails.

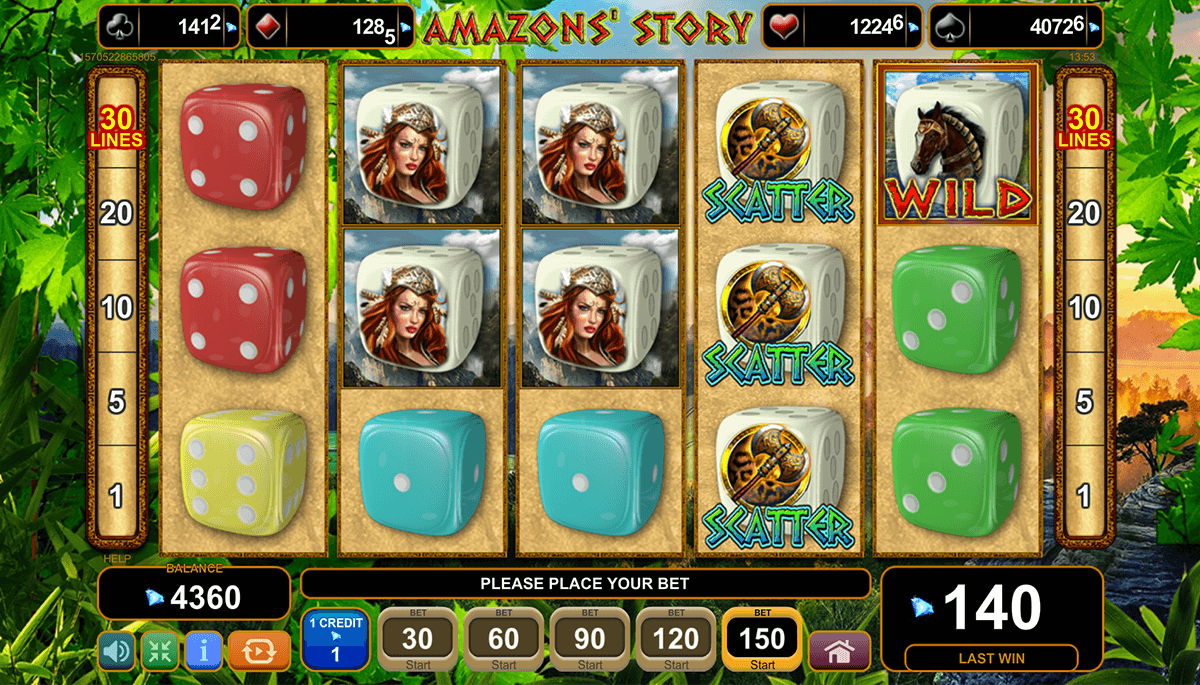

Notice how the story spine allows us to compress a complex film into a series of simple beats. In the next exercise you'll have a chance to try this out. You can fit your three favorite films into the story spine, as well as generate spines for stories you may want to create. Video on YouTube Standard Youtube. Weekly Diamond VIP for $4.99 offers a weekly subscription, unlocks 20 spins, 30 gems,1 mana on a daily basis and gain extra spins and coins reward in-game wheel event. Monthly Diamond VIP for $16.99 offers a monthly subscription, unlocks 20 spins, 30 gems, 1 mana on a daily basis and gain extra spins and coins reward in-game wheel. 120 Free Spins For Real Money Enter For Your Chance To Win. Enter For Your Chance To Win 120 Free Spins For Real Money At The Best Online Casinos. Win big with this online casinos offer no deposit bonus codes. Enter For Your Chance To Win 120 Free Spins.

120 Free Spins Story Generator

Since posting the story, a number of people have contacted us regarding rule number 4 on the list, also known as ‘The Story Spine’:

- With Free Daily Spins its as easy as one, two three. And we'll give you 100 free spins for joining with no deposit required. Once you join the more you deposit and play, the more free.

- If you’re looking for casinos that offer a 200 free spins bonus as part of their welcome package, then you’re in the right place. We have hunted high and low to bring you all these bonuses in one handy list. Many players love to claim free spins and consider.

Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

Reports were that this tip did not originate with Pixar but instead with writer/director/teacher Brian McDonald. Intrigued, we contacted Brian to find out more. He replied as follows:

I should clear up that the story spine (Once upon a time…) is not mine. I think many people first learned it from me because of my books, classes and lectures I have given over the past dozen years or so. It did not originate with Pixar either. I looked for the origin of these steps when I was writing my book, but never found it and I say so in the book. It has been used in impov as an exercise where is where I first learned it. I know a guy looking for the origin, but he’s not having any luck either.**

Brian added that in the original story spine tweet a step was actually left out. The final step should be And ever since that day… As Brian says, the list ‘keeps getting copied with this missing step and it’s an important step.’

Brian, an award-winning filmmaker in his own right, has taught his story structure seminar at Pixar, Disney Feature Animation and Lucasfilm’s ILM. For readers wanting to know more about The Story Spine, the following article by Andy Goodman explores in further detail these 7 simple steps for building more engaging stories.

Andrew Stanton knows a thing or two about telling stories. Having written screenplays for Toy Story, Finding Nemo, and WALL-E – movies that have grossed billions of dollars worldwide for Pixar Studios – he’s earned the title Master Storyteller. So when Stanton says that he got stuck while writing a story and a certain book got him un-stuck, I want to read that book.

Which I did, and now I strongly recommend you read it, too. Because even if you’re not in the screenplay-writing business, Invisible Ink: A Practical Guide to Building Stories that Resonate, can help you stop staring at that blank page and start writing.

Brian McDonald, the book’s author, began studying stories by audio-taping The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Newhart and other classic sitcoms that he watched at home after school. McDonald transcribed and analyzed the dialogue to learn precisely what made these thirty-minute stories tick. At 21, he moved to Los Angeles to find work as a writer and director but ended up on the special effects crews of such forgettable horror films as Return of the Living Dead II and Night of the Creeps.

Like many before him, McDonald eventually struck out on his own, financing his first film, White Face, out of his own pocket. A mockumentary about racism (with white face clowns playing the role of Oppressed Minority), the 14-minute movie made up for its $1,000 budget with a great story and lots of laughs, and it captured the audience prize at the Slamdance Film Festival in 2001.

McDonald, 45, currently teaches screenwriting at the 911 Media Arts Center in Seattle, occasionally returning to California to lead workshops at Pixar Studios, Industrial Light & Magic and Disney Animation. He published Invisible Ink last year, and when we spoke recently, we talked at length about Chapter II, ‘Seven Easy Steps to a Better Story.’ Before we began, McDonald insisted we be clear on one point. ‘I didn’t make this up,’ he told me, referring to the seven-step model. McDonald says he learned the steps from Matt Smith, an improvisational actor who learned them from Joe Guppy, another improv veteran.

Regardless of the original source, the seven sentences that follow can help you start writing a story and build it, scene by scene, to its climax and resolution. And it all begins with those familiar four words:

Once upon a time…

Whether you use these exact words or not, this opening reminds us that our first responsibility as storytellers is to introduce our characters and setting – i.e., to fix the story in time and space. Instinctively, your audience wants to know: Who is the story about? Where are they, and when is all this taking place? You don’t have to provide every detail, but you must supply enough information, says McDonald, “so the audience has everything it needs to know to understand the story that is to follow.”

And every day…

With characters and setting established, you can begin to tell the audience what life is like in this world every day. In The Wizard of Oz, for example, the opening scenes establish that Dorothy feels ignored, unloved, and dreams of a better place “over the rainbow.” This is Dorothy’s “world in balance,” and don’t be confused by the term “balance.” It does not imply that all is well – only that this is how things are.

Until one day…

Something happens that throws the main character’s world out of balance, forcing them to do something, change something, attain something that will either restore the old balance or establish a new equilibrium. In story structure, this moment is referred to as the inciting incident, and it’s the pivotal event that launches the story. In The Wizard of Oz, the tornado provides the inciting incident by apparently transporting Dorothy far, far away from home.

And because of this…

Your main character (or “protagonist”) begins the pursuit of his or her goal. In structural terms, this is the beginning of Act II, the main body of the story. After being literally dropped into the Land of Oz, Dorothy desperately wants to return home, but she is told that the only person who can help her lives far away. So she must journey by foot to the Emerald City to meet a mysterious wizard. Along the way she will encounter several obstacles (apple-throwing trees, flying monkeys, etc.) but these only make the narrative more interesting.

And because of this…

Dorothy achieves her first objective – meeting the Wizard of Oz – but this is not the end of her story. Because of this meeting, she now has another objective: kill the Wicked Witch of the West and deliver her broomstick to the Wizard. “In shorter stories,” says McDonald, “you may have only one ‘because of this,’ but you need at least one.”

Until finally…

We enter Act III and approach the story’s moment of truth. Dorothy succeeds in her task and presents the Wizard with the deceased witch’s broom, so now he must make good on his promise to help her return to Kansas. And this he does, but not quite in the way we initially expect.

And ever since that day…

Once we know what happened, the closing scenes tell us what the story means for the protagonist, for others in the narrative, and (not least of all) for those of us in the audience. When Dorothy awakens in her own bed and realizes she never actually left Kansas, she learns the lesson of the story: what we’re looking for is often inside us all along.

The next time you get stuck while writing a story, try walking your narrative through these steps. Even if your characters aren’t following a yellow brick road, the seven sentences above can probably help you get where you’re going. And your little dog, too.

120 Free Spins Story Game

This article was written by Andy Goodman and originally published in free-range thinking in June 2010. Reproduced with permission. Andy Goodman is the co-founder of The Goodman Centerand author of Storytelling as Best Practice.

Brian McDonald blogs at Invisible Ink and can be followed on Twitter. He is the author of Invisible Ink, The Golden Theme and Ink Spots.

Thanks to Brian and Andy for allowing us to share their work.

** UPDATE: via the comments below we have since learned that The Story Spine was created by Kenn Adams in 1991. Read Kenn’s guest post Back to the Story Spine.